Clair Obscur review: J'RPG

Some people just need killing.

In ye olde Japanese roleplaying game tradition, there is a real bastard awaiting you at the end of the world in Clair Obscur: Expedition 33.

[Mild mechanical spoilers follow for an optional boss in Clair Obscur: Expedition 33’s third act.]

The good news is that you won’t simply stumble into him. No, first you’ll traverse an impossible wasteland of dilapidated structures, all strangely preserved in melting amber like an unfinished draft of an already-dead world.

Its only denizens are the shambling husks of eldritch creations strewn about. Actually, maybe it’s better to think of them as mistakes. Things that exist despite themselves.

Then, there’s the Abyss. You exit a cave system to an incorporeal bridge to nowhere, which isn’t as hopeless as it seems; your destination is below.

Down

Down

Down

You fall for so long that you fear the sun itself will extinguish before you reach the bottom.

And then it does.

Now you’re at the bottom, where an uncountable number of gleaming, towering 100-foot swords stand in memoriam.

But for whom?

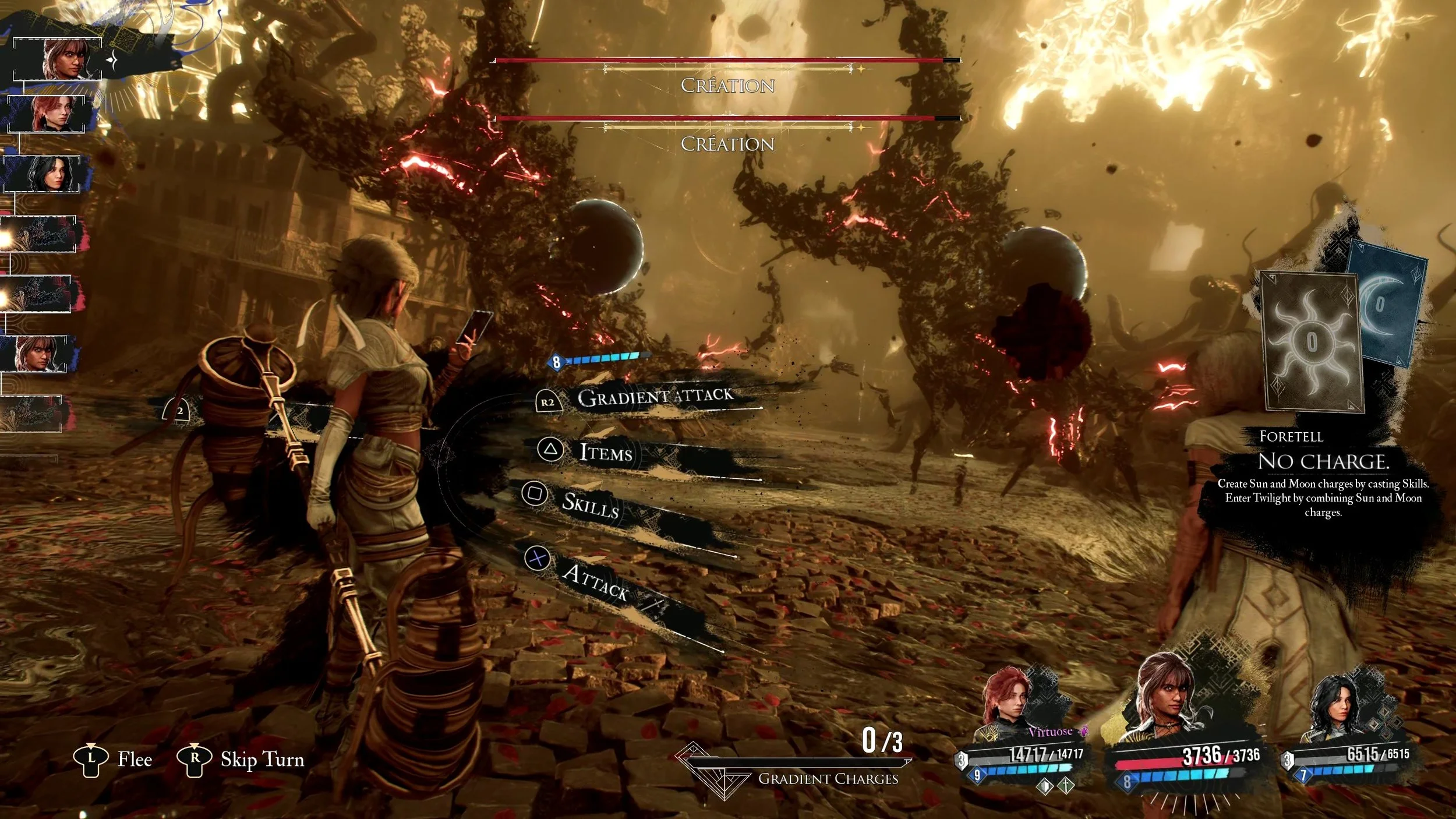

After a while, you see him, a man who is, at a minimum, two men wide, with Super Saiyan 3 hair and the battle posture of all the most annoying From Software guys you know. He just looks like he has two health bars. And wouldn’t you know it…

On the first day, I never even saw the second health bar. The man didn’t just remove my shields, but he stole them for his own use. He let loose a barrage of strikes with just-varied-enough timing that made parrying hell. And, because he could, he ended each round by reducing the HP of my healthiest party member to 1.

I saved the best detail for last. If the man reduces a party member’s health to 0 while he has actions remaining, he’ll completely erase them from existence. No phoenix downs. No magic. No nothing.

On the second day, I realized that the first had been a farce. What I thought was one sword had been two. He swung his sword(s) and the world was cut open.

But let’s say you endure this vorpal punishment long enough to reduce him to ~40 percent of his health. What’s your reward?

He erases your party from existence, regardless of how much health they have.

[end of mild mechanical spoilers]

In Clair Obscur, your remaining expeditioners can take the field if your first party is wiped out, so this isn’t a lose condition, necessarily. But it *is* a mental lose condition the first time it happens to you.

And the second.

And the third.

On the third day, I was still stacking Ls like the worst game of Tetris you’ve ever seen. I had his parry timing down for the vast majority of his attacks, but one miss still spelled doom for my team of glass cannons.

I tinkered with balanced approaches. I experimented with defensive builds that focused on keeping my entire party as healthy as possible.

None of it worked.

I questioned not just my philosophy with this game, but my entire sense of self.

Then, inspiration struck: What if I just leaned all the way into the glass cannon approach?

After staring at menus for no less than 10 minutes, I devised a plan that would concentrate every bit of firepower I’d accrued across 70 hours of play into a single strike. It felt like I was doing honest-to-God science. After running trials, carefully selecting from a Sears catalog of equippable abilities, testing the results in the field, crunching the numbers and refining where possible, I found a winning strategy that let me grant that bastard the peace that he had not once afforded me.

Limit break

For as long as I can remember, damage received and taken in most JRPGs has been arbitrarily capped at 9,999. It was probably a lot less arbitrary in 1987 with the first Final Fantasy and its many hardware limitations on the NES, but it’s a figure that many, many games have settled on in the decades since.

Clair Obscur upholds this tradition for two of its three acts, until

This metaphorical removal of the training weights in the game’s third act is a microcosm of what makes Clair Obscur so great; it knows when to hold on to tradition, and it knows when to let go.

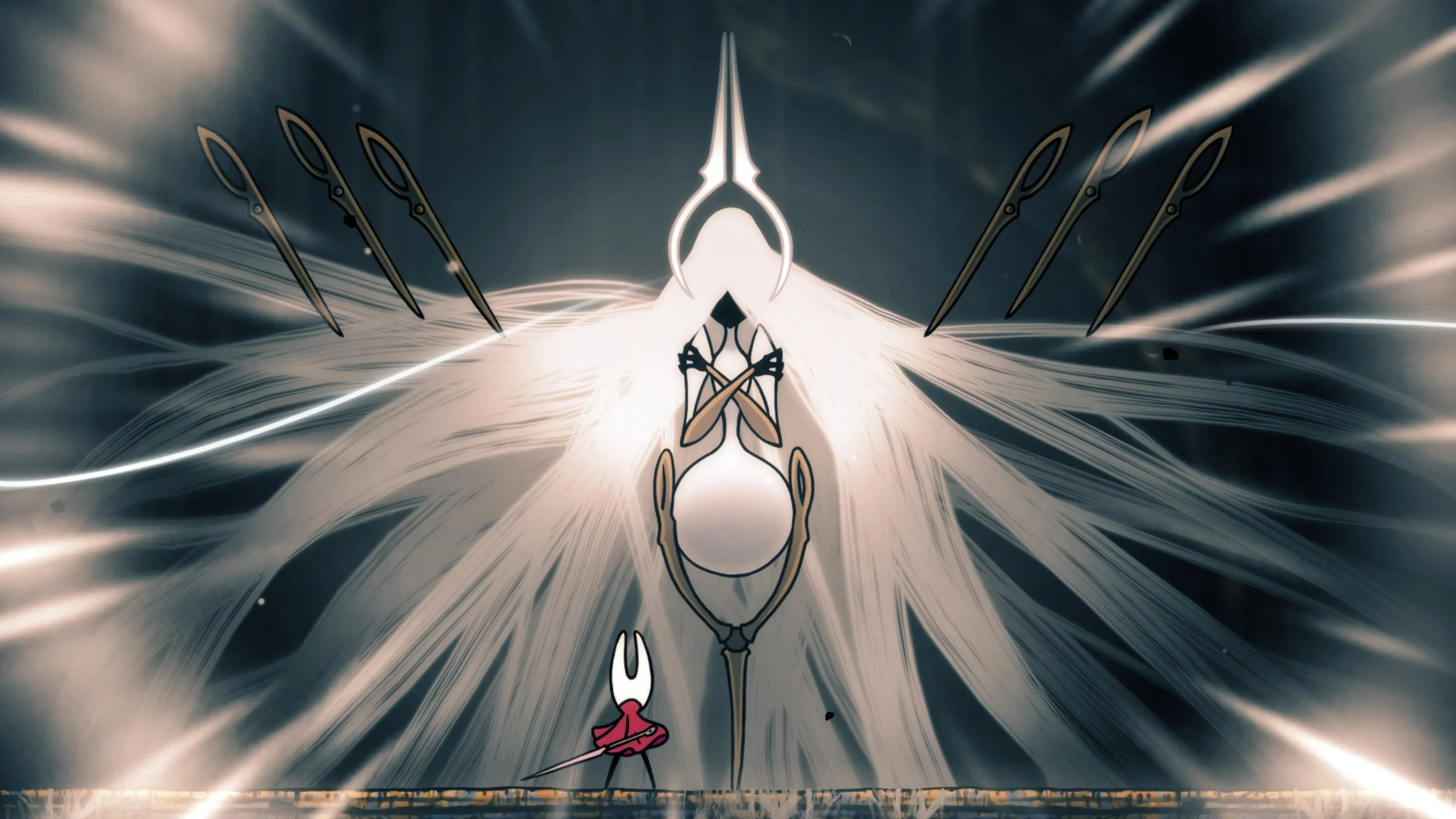

If you pay any attention to video games coverage, you’re going to see a lot of folks (rightly) praising Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 and its timing-based combat system, built upon a scaffolding of Mario RPGs, Shadow Hearts, Valkyrie Profile, Sea of Stars, and others.

Clair Obscur does more than give you a button prompt for attacking and defending. For starters, it deftly sidesteps the inherent awkwardness of needing to learn the moveset of each new enemy before you can capably deal with their attacks. First-time developer Sandfall Interactive manages this by giving you a dodge as well as a parry, the former of which has a far more generous invincibility window at the cost of forgoing an opportunity to counterattack.

The genius part, though, is that there’s a regular dodge, which requires less precision, and a perfect dodge, which has the exact same timing as a parry. In other words, Clair Obscur allows you to dodge new enemies you encounter in relative safety until you perfect the timing. Then, you can take the training weights off and switch to parries to cash in on those incredibly satisfying counterattacks.

Of course, the beauty of the interplay between Clair Obscur’s systems and its mechanics is that you don’t need to have majored in killing Sword Saint Isshin to finish the game. There’s a build for everything, including dodging, getting hit and—I mean this quite literally—dying.

It has a town of silly little guys in it.

I could write 3,300 words about pictos and luminas, the means by which Clair Obscur achieves its remarkable flexibility. Pictos are accessories that bestow a specific ability upon an expeditioner, much like how Final Fantasy IX’s magic stone system granted abilities through weapons. Survive four battles with a pictos equipped and the entire party gains access to its corresponding lumina, which grants the effect without having to equip the pictos (expeditioners can only equip three pictos at a time).

Some are as straightforward as Anti-Burn (you’re immune to the burn status effect). Others, like Auto-Death (kills the user at the start of battle), only reveal their full potential in time. What looks like sabotage at the outset becomes the first domino in a Rube Goldberg machine that can leave enemies teetering on the brink of defeat before you’ve even taken your first turn. There are hundreds of synergies to discover, and you’ll gain more luminas to play with as you progress for even more absurd combos.

But I want to talk about another similarity Clair Obscur shares with Final Fantasy IX.

It has a town of silly little guys in it.

Conde Petie is a settlement built atop two titanic tree roots that serves as the last checkpoint before reaching the Iifa Tree, Final Fantasy IX’s version of Yggdrasil, or the World Tree. But all you need to know is that it’s full of silly little dwarves with comically-thick Scottish accents (Rally-ho!).

Clair Obscur doesn’t have any dwarves. But it does have Gestrals, strange paint-brush humanoids who have built a society in Gestral Village, a place where it’s perennially on-sight and everyone throws hands.

Even the children.

Each villager wants to fight you, scream at you in franken-French, or both. Participate at your own risk, but don’t incur the wrath of the village chef (chef = chief in French), a being powerful enough to kick you into the sun.

Everyone in Gestral Village is funny, and you will laugh an unexpected amount throughout your journey to the Paintress. Clair Obscur’s blue mage (an archetype of party member who repurposes enemy skills for their own use) activates his magic by collecting the feet of his fallen foes.

That was one of the worst sentences I’ve ever written, but it’s true; that’s just how it works.

Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 is delightfully weird and also one of the funniest RPGs I have ever played, which is good because the core premise of Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 is extremely not.

For those who come after

A mysterious being called the Paintress exists on the other end of the world from Lumiere, the last very French refuge of humanity. Each year, she paints a number on a massive monolith, and everyone who is that age dies. And each year, that number decreases by one.

The remaining humans send out a group of volunteers to journey to the other side of the continent to deal with the Paintress before there’s no one left to send.

Expedition 33 is not named as such because it is the 33rd expedition, but rather because the oldest humans left to send are 33 years old.

An expeditioner’s goal is to either eliminate the Paintress, or make the path for their successors easier to tread.

No expeditioner has ever returned to Lumiere alive.

JPRGs and death march narratives go together like tonberries and knives. Final Fantasy X, the game that has seemingly drawn the most comparisons to Clair Obscur, is similarly about a doomed priestess and her entourage on a pilgrimage to fight god.

Xenoblade Chronicles 3 features star-crossed lovers and their band of friends, all of whom have 10-year lifespans (it’s complicated), and their struggle to escape a generational war. Oh, and they have to kill two dozen gods (I told you it’s complicated).

Lost Odyssey is about a sad immortal amnesiac and… you see where I’m going with this.

Clair Obscur isn’t necessarily sadder than those games. But it certainly is more affecting, thanks in no small part to emotional performances from Jennifer English as Maelle, a little badass who you will instantly adopt into your heart.

There’s also Charlie Cox (yeah, that one) as Big Brother Gustave, Andy Serkis as… a guy you’ll meet later, and Ben Starr as…another guy you’ll meet later.

Most impressive among the big names is relative newcomer Kirsty Rider as Lune, Fictional Woman of the Year for whom footwear is always optional. If IMDB is correct, Lune is Rider’s first major role in video games, which I suppose would make this her Illmatic.

The performances are delightful, but so is the material that they are given to work with. Much of this can be attributed to the fact that the Sandfall Interactive writing team understands that mystery itself is a propulsive force. Clair Obscur’s script doles out information at such a tantalizing pace that you can’t help but want to press on for answers.

Even when it’s 3 a.m. and you have work the next day. We continue.

Its central conceit is the linchpin holding together every other facet of its design, and it’s so strong that even elements of design that would be considered banal in other games are elevated here. You’ll occasionally find journals left behind by previous expeditions. And, sure, what post-2007 game hasn’t deployed an audio log? But Clair Obscur dares to ask: What if audio logs were simply good?

What if we could introduce a named character, whose face you’ll never see, and gave them a compelling and human story within the 45 seconds comprising their final moments on Earth? What if we made you laugh at how silly earlier expeditions were, like Expedition 50, who just built a big ol’ wheel and (unsuccessfully) rolled their way to the Paintress?

Wait…they don’t love you like I love you.

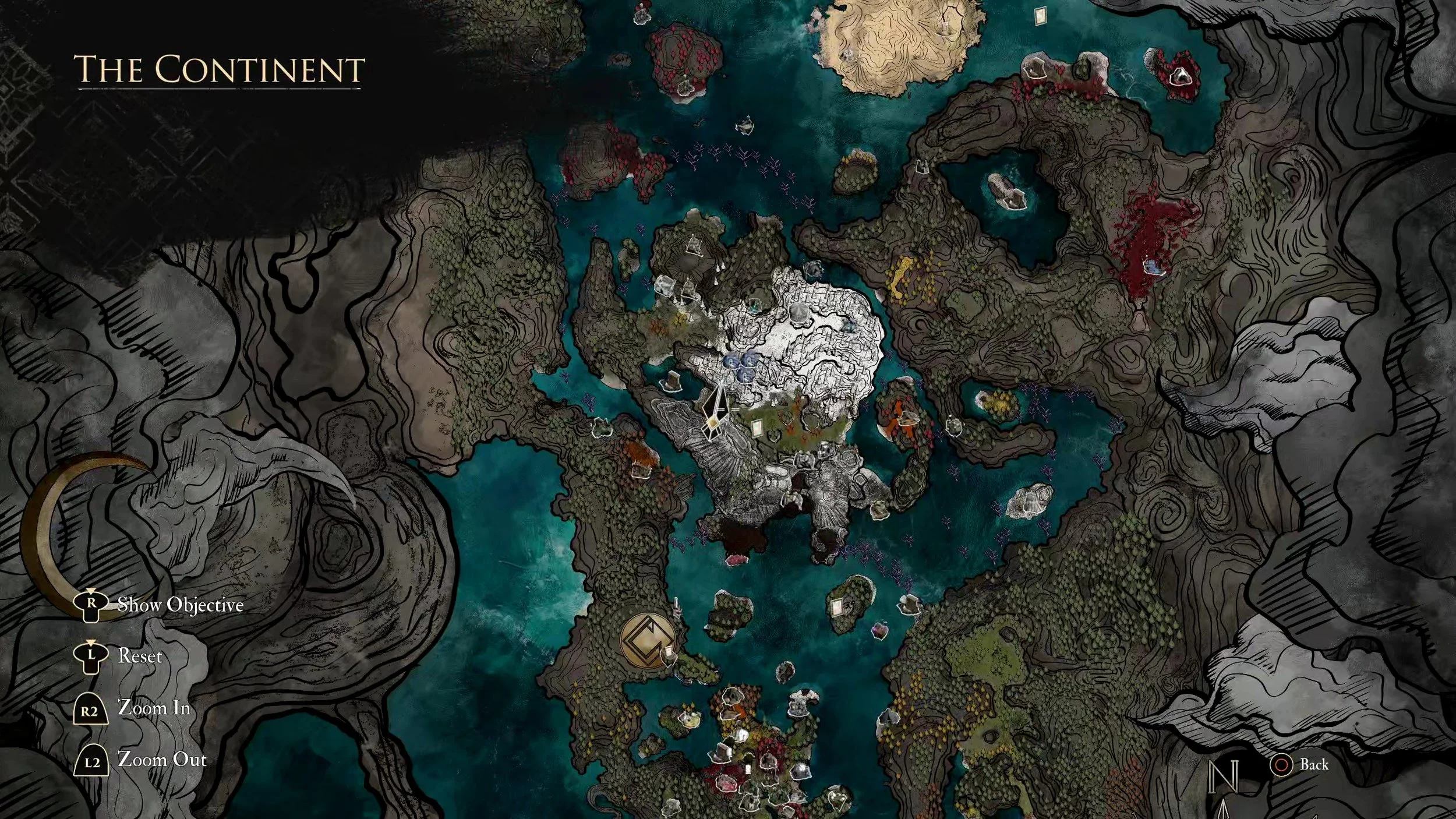

I knew Clair Obscur was in good hands when Sandfall highlighted their world map in the Xbox Developer Direct stream back in January. In the same way that a fantasy book is only elevated by the existence of a world map in its opening pages, and the assurance that its author took the time to consider where everything goes, so too is an RPG only improved by the inclusion of a world map.

Clair Obscur doesn’t do anything special with its world map, but you’ll be grateful for it as the game drastically expands in scope in later acts. It took me a little more than 70 hours to get every achievement, and more than half of that time was spent on optional quests. I had forgotten what it felt like to poke and prod at every weird structure, funny-looking rock or weird merchant I encountered in an overworld.

And like the best open-world games, you are immediately able to stumble into an encounter meant to be tackled in another 20 levels or so. But because every single attack in the game has a counter, there’s no boss you can’t defeat, even from the very beginning. The sickos at Sandfall know this, because they sprinkle a handful of demanding optional boss encounters throughout the world. Some of them are minigames with their own unique mechanics, such as a giant sapling with a horrific face that you must kill before the walls close in (not unlike the recurring Demon Wall/Gate in the Final Fantasy series). These encounters are so creative and fun that the battle is often just as much of an incentive for exploration as the rewards they provide.

This all culminates in the bastard, of course, but there’s a lot more to discover along the way, including some truly unhinged minigames (overseen by Gestrals, of course) and 17 quadrillion outfits.

Tomorrow comes.

There’s so much I haven’t even told you, but it’s better for you to experience those things yourself. I wish I could’ve talked more about the incredible music, or the clever way this game solves the 99 Potions Dilemma (consumable healing and support items are refilled at checkpoints, not unlike your Dark Souls estus flask).

Sandfall Interactive is so obviously composed of students of JRPG history who collectively knew which traditions to hold onto, and which ones could be discarded or reworked entirely. It’s a loud repudiation of the notion that turn-based RPGs are an inherent turnoff to mainstream audiences, and it deserves every accolade it is sure to collect come award season.

While I admire Square Enix’s insistence on reinventing itself with each numbered Final Fantasy entry, I hope Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 stands as a bold reminder that there was an awful lot of material left on the JRPG cutting room floor.